Let f be an arbitrary (complex-valued or real-valued) function defined on an semi-infinite interval [0, ∞);

then the integral

\begin{equation} \label{EqLaplace.1}

f^L (\lambda ) = \left( {\cal L} \,f \right) (\lambda ) = \int_0^{\infty} f(t)\,e^{-\lambda t} \,{\text d} t = \lim_{N\to +\infty} \int_0^{N} f(t)\,e^{-\lambda t} \,{\text d} t

\end{equation}

is said to be the

Laplace transform of

f provided that the integral \eqref{EqLaplace.1} converges for some value

\( \lambda = s \) of a parameter λ. Therefore, the Laplace transform of a function

(if it exists) depends on a parameter λ, which could be either a real number or a complex number. Saying that

a function

f(

t) has a Laplace transform

fL means that for some λ =

s, the limit

\[

f^L (\lambda ) = \lim_{N\to \infty} \, \int_0^{N} f(t)\,e^{-\lambda t} \,{\text d} t

\]

exists. From the definition of integral, it follows that the Laplace transform

does not depend on the values of an integrated function at a discrete number

of points. Therefore, the Laplace transform can map different functions into

the same output. Since application of the Laplace transformation to

differential equations requires also the inverse Laplace transform, we need a

class of functions that is in bijection relation with its Laplace transforms.

The integral that defines the Laplace transform does not have to

converge. For example, neither

\( {\cal L} \left[ 1/t \right] \) nor

\( {\cal L} \left[ e^{t^2} \right] \) exist.

There are known some sufficient conditions

guaranteeing the existence of

\( {\cal L} \left[ f(t) \right] . \)

Theorem 1:

If a function f is absolutely integrable over any finite interval from

\( [0, \infty ) ; \) and the Laplace integral \( \int_0^{\infty} f(t)\,e^{-\lambda t} \,{\text d} t \)

converges for some complex number

\( \lambda = s , \) then it converges in the

half-plane \(

\mbox{Re}\,\lambda > \mbox{Re}\, s , \)

i.e., in \( \left\{ \lambda \in \mathbb{C} \, : \, \Re\,

\lambda > \Re\, s \right\} . \)

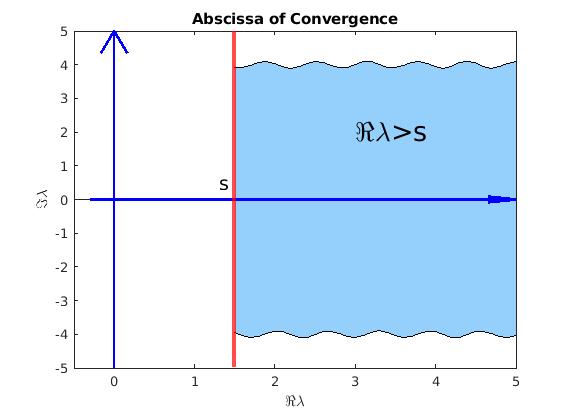

Definition:

The smallest real number σ∈ℝ for which the integral \( \int_0^{\infty} f(t)\,e^{-\sigma t} \,{\text d} t \)

converges is called the abscissa of convergence of the function f.

|

|

We plot the abscissa of convergence and the domain where the Laplace transformation converges.

clear all;

clear vars;

red=[1 0 0];

plotInterval = 1.5:0.1:8;

areaInterval = 1.5:0.1:6;

fh = figure;

ah = axes(fh);

g=@(x) -4+0.1*sin(10*x);

f=@(x) 4 + 0.1*cos(10*x);

plot(ah,plotInterval,g(plotInterval))

hold on

H1=area(ah,areaInterval,g(areaInterval))

set(H1,'Facecolor',[0.5843 0.8157 0.98821]);

hold on

plot(ah,plotInterval,f(plotInterval))

hold on

H2=area(ah,areaInterval,f(areaInterval));

set(H2,'Facecolor',[0.5843 0.8157 0.9882]);

p1 = [0 -5];

p2 = [0 5];

dp = p2-p1;

hold on

H3=quiver(p1(1),p1(2),dp(1),dp(2),0);

set(H3,'Linewidth',2);

set(H3,'color',[0 0 1]);

hold on

s=xline(1.5,'Linewidth',3,'Color',red);

p3 = [-0.3 0];

p4 = [5 0];

dt = p4-p3;

hold on

H4=quiver(p3(1),p3(2),dt(1),dt(2),0);

set(H4,'Linewidth',2);

set(H4,'color',[0 0 1]);

xlim([-0.5,5])

ylim([-5,5])

xlabel('\Re\lambda')

ylabel('\Im\lambda')

txt1='s'

t1=text(1.3,.5,txt1)

t1.FontSize=14

txt2= '\Re\lambda>s';

t2=text(3,2,txt2);

t2.FontSize=20;

% define plot intervals

% plot into one figure/axes

title('Abscissa of Convergence')

|

|

Abscissa of convergence and the domain of convergence for a Laplace transformation.

|

|

matlab code

|

Theorem 2: The Laplace transform is a linear operator.

In most applications

t is the time and the domain of the real variable

t is the

time domain. But the product λ

t in

\( e^{-\lambda\, t} \) is necessarily a pure number. One way to see this is by expanding the exponential function into the Taylor series

\[

e^{-\lambda\, t} = 1 - \lambda t + \frac{1}{2!}\, (\lambda t)^2 - \frac{1}{3!}\, (\lambda t)^3 + \cdots .

\]

If λ

t had any units, such as millimeters or seconds, the terms in the series would all have different units and summation would make no sense. Since λ

t is a pure number, λ must have the units of 1/

t. Hence, the product λ

t represents a dimensionless number (such as cycles) and λ has the units of frequency. It is often advantageous to let λ be complex, and consider it as the

complex frequency. Then the set of values of λ is referred to as the

frequency domain.

Definition: A function

f is said to be

piecewise continuous or

intermittent on a finite closed interval [𝑎,

b] if

the interval can be divided into finitely many subintervals so that

f(

t) is continuous on each subinterval and

approaches a finite limit at the end points of each subinterval from the interior.

A function is said to be

piecewise continuous or

intermittent on the infinite interval if it is piecewise continuous on every finite

compact subinterval.

For our needs, we will use more restrictive definition of the intermittent function.

A function

f(

t), defined on semi-infinite interval [0, ∞), is piecewise continuous if this interval can be broken into finite number of pieces

\[

[0, \infty ) = [0, b_1) \cup (a_2 , b_2 ) \cup \cdots \cup (a_m, \infty ) ,

\]

so that the function

f(

t) is continuous on each of them and has finite limit values at the endpoints. A piecewise continuous function can be defined as

\[

f(t) = \begin{cases}

f_1 (t) , & \ 0 < t < b_1 ,

\\

f_2 (t) , & \ a_2 < t < b_2 ,

\\

\vdots

\\

f_m (t) , & a_m < t < \infty ,

\end{cases}

\]

where each function

fk(

t),

k = 1, 2, … ,

m, is continuous on the interval (𝑎

k,

bk) and has finite limit values at 𝑎

k and

bk.

We do not specify the values of the function

f(

t) at endpoints

(𝑎

k,

bk) because we are going to apply the Laplace transformation to such intermittent functions; recall that the integral is not sensitive to the values of the function at a finite number of points. So wherever the function has values at the points of discontinuities, its Laplace transform does not depend on these values.

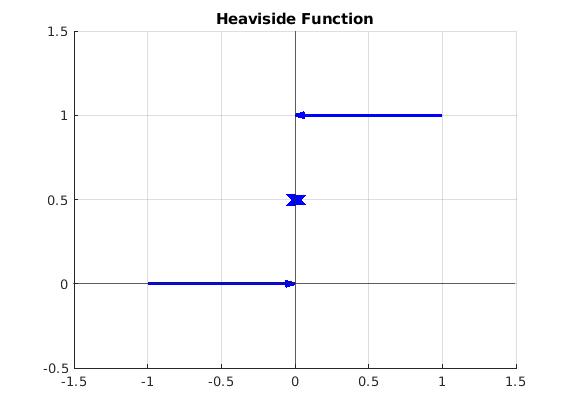

Definition: The

Heaviside function H(

t) is the unit step function:

\begin{equation} \label{EqLaplace.2}

H(t) = \begin{cases} 1, & \quad t > 0 , \\

1/2, & \quad t=0, \\

0, & \quad t < 0. \end{cases}

\end{equation}

>> ans =

0.5000

|

|

We plot the Heaviside function:

clear all;

fh=figure;

x1=xline(0,'Linewidth',1);

t=yline(0,'Linewidth',1);

title('Heaviside Function')

hold on

xlim([-1.5,1.5])

ylim([-0.5,1.5])

hold on

p1 = [1 1]; % First Point

p2 = [0 1]; % Second Point

dp = p2-p1; % Difference

hold on

H1=quiver(p1(1),p1(2),dp(1),dp(2),0);

set(H1,'Linewidth',2);

set(H1,'color',[0 0 1]);

hold on

p3 = [-1 0];

p4 = [0 0]

dt=p4-p3;

hold on

H2=quiver(p3(1),p3(2),dt(1),dt(2),0);

set(H2,'Linewidth',2);

set(H2,'color',[0 0 1]);

hold on

x_pos =0;

y_pos =0.5;

plot(x_pos,y_pos,'x','Markersize',10,'linewidth',10,'MarkerEdgeColor',[0 0 1]);

hold on

grid

|

|

Heaviside function.

|

|

matlab code

|

It is known in calculus that if a function

f is intermittent on a finite closed (compact) interval, then it is integrable on that interval. But for integrability of the product

\( f(t)\, e^{-\lambda t} \) on the semi-infinite interval [0, ∞), we need a stronger condition than piecewise continuity. The following definition provides a sufficient condition on the function

f to possess the Laplace transform.

Definition:

A function

\( f(t), \ t \in [0, \infty ) \) is said to be a

function-original

if it has a finite number of points of discontinuity (finite jumps) on every finite subinterval of

\( [0, \infty ) \) and it grows not faster than an exponential, that is

\begin{equation} \label{EqLaplace.3}

| f(t) | \le M\, e^{ct} \qquad \mbox{for} \quad t > T,

\end{equation}

with some constants

c,

M, and

T. Moreover, we assume that at points of discontinuity the

values of a function-original are equal to the corresponding mean values:

\begin{equation} \label{EqLaplace.4}

f(t) = \frac{1}{2} \left[ f(t+0) + f(t-0) \right] = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0, \ \varepsilon \ge 0} \,

\frac{1}{2} \left[ f(t+\varepsilon ) + f(t-\varepsilon ) \right] .

\end{equation}

The Laplace transform of such a function is called the

image.

In practical applications, the mean value property \eqref{EqLaplace.4} is not essential---it is used mostly in theoretical analysis. We usually do not pay attention to values of the function-original at the points of discontinuity (if any). However, be aware that the inverse Laplace transformation (as well as Fourier) restores the function with the mean value property. Therefore, the inverse Laplace transform automatically defines a function that has the property \eqref{EqLaplace.4}.

Definition:

We say that a function f is of exponential order if the inequality \( | f(t) | \le M\, e^{ct} \) holds for some constants

c, M, and T. We abbreviate this as

\( f = O\left( e^{ct} \right) \) or

\( f \in O\left( e^{ct} \right) . \)

A function f is said to be of exponential order α, or

eo(α) for abbreviation, if

\( f = O\left( e^{ct} \right) \) for any real number c > α, but not when

c < α.

Theorem 3: The Laplace transform exists for a function of exponential order, and tends to zero at infinite point.

Theorem 4: The Laplace transform establishes a one-to-one correspondence between

functions-originals and their images. ⧫

Example 1:

The Laplace transforms of the unit function and the Heaviside function are the same and equal to

\[

{\cal L} \left[ 1 \right] = {\cal L} \left[ H(t) \right] = \int_0^{\infty} \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{1}{\lambda} .

\tag{2.1}

\]

Note that the Laplace transform (2.1) does not depend on the value of the Heaviside function at

t = 0.

syms t s

laplace(1,t,s)

>> ans =

1/s

Now we find the Laplace transform of shifted Heaviside function:

syms t s

syms a positive

laplace(heaviside(t-a),t,s)

>> ans =

1/(s-a)

Note that matlab assigns the parameter "s" (by default), but not λ. You can specify the parameter output:

syms t lambda

laplace(1,t,lambda)

>> ans =

1/lambda

■

Example 2:

We find the Laplace transform of the power function:

\[

{\cal L} \left[ t^p \right] = \int_0^{\infty} t^p \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{1}{\lambda^{p+1}} \,\int_0^{\infty} \tau^p \,e^{-\tau} \,{\text d} \tau = \frac{\Gamma (p+1)}{\lambda^{p+1}} ,

\tag{2.1}

\]

where

\( \Gamma (\nu ) = \int_0^{\infty} t^{\nu -1} \, e^{-t} \, {\text d} t \) is the

Gamma-function of

Euler.

Let us consider a particular case when p = −½.

The function has infinite discontinuity at t = 0. Hence, this function is not piecewise continuous on [0, ∞). However, its Laplace transform exists and can be found by

substitution λt = x², which gives

\[

{\cal L} \left[ t^{-1/2} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} t^{-1/2} \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\lambda}} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-x^2} \,{\text d} x = \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\lambda}}

\tag{2.2}

\]

because

\( \lambda\,{\text d}t = 2x\,{\text d} x . \) With a similar substitution, we obtain

\[

{\cal L} \left[ t^{1/2} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} t^{1/2} \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{2}{\lambda\,\sqrt{\lambda}} \int_0^{\infty} x^2 \,e^{-x^2} \,{\text d} x = \frac{1}{2\lambda}\,\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\lambda}} .

\tag{2.3}

\]

Note that the Laplace transform of the power function tp (t ≥ 0) exists only when p > -1. Otherwise, the Laplace transform does not exist because the corresponding integral diverges.

This example shows that the Laplace transform exists for a wider class of functions than functions-original.

syms t lambda

a=t^(-1/2);

laplace(a,t,lambda)

% or directly

laplace(t^(-1/2), t, s)

laplace(t^(1/2), t, s)

>> ans =

pi^(1/2)/lambda^(1/2)

In general, we have

syms t s p

laplace(t^p,t,s)

>> ans =

piecewise(-1 < real(p) | 1 <= p & in(p, 'integer'), gamma(p + 1)/s^(p + 1))

■

Example 3:

The Laplace transform of the exponential function is

\[

{\cal L} \left[ e^{at} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} e^{at} \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{1}{a - \lambda} .

\tag{3.1}

\]

matlab confirms:

syms t a lambda

ex=exp(a*t);

laplace(ex,t,lambda)

% or directly

laplace(exp(a*t), t, lambda)

>> ans =

1/(a - lambda)

Its abscissa of convergence is λ = Re𝑎.

■

Example 4:

To find the

Laplace transform of the trigonometric functions, we recall that they are

real and

imaginary parts of pure imaginary exponential functions (known as Euler's formula):

\[

\sin (at) = \Im\, e^{{\bf j} at} \qquad\mbox{and} \qquad \cos (at) = \Re\, e^{{\bf j} at} ,

\tag{4.1}

\]

where

j is the unit vector in positive vertical direction on the complex plane, so

j2 = -1. As usual, ℑ = Im is the imaginary part of a complex number; correspondingly, ℜ = Re is the real part of a complex number. So ℑ(𝑎 +

jb) =

b and ℜ(𝑎 +

jb) = 𝑎.

Let us take 𝑎 in Eq.(4.1) to be pure imaginary, so 𝑎 ↦ j𝑎. Then

\[

{\cal L} \left[ e^{{\bf j}at} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} e^{{\bf j}at} \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \frac{1}{{\bf j}a - \lambda} =

\frac{\lambda +{\bf j}a}{\left( {\bf j}a - \lambda \right) \left( \lambda +{\bf j}a \right)} = \frac{\lambda +{\bf j}a}{\lambda^2 + a^2} .

\tag{4.2}

\]

Extracting the real part of (4.2), we obtain the Laplace transformations of trigonometric cosine function:

\[

\Re {\cal L} \left[ e^{{\bf j}at} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} \cos (at) \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \Re \frac{1}{{\bf j}a - \lambda} = \Re \frac{\lambda +{\bf j}a}{\lambda^2 + a^2} = \frac{\lambda}{\lambda^2 + a^2} .

\tag{4.3}

\]

matlab confirms:

syms t a lambda

c=cos(a*t);

laplace(c,t,lambda)

>> ans =

lambda/(a^2 + lambda^2)

Similarly, taking the imaginary part, we get

\[

\Im {\cal L} \left[ e^{{\bf j}at} \right] = \int_0^{\infty} \sin (at) \,e^{-\lambda\,t} \,{\text d} t = \Im \frac{1}{{\bf j}a - \lambda} = \Im \frac{\lambda +{\bf j}a}{\lambda^2 + a^2} = \frac{a}{\lambda^2 + a^2} .

\tag{4.4}

\]

matlab confirms:

syms t a

laplace(sin(a*t))

>> ans =

a/(a^2 + s^2)

Here ℜ denotes the real part of a complex number, so ℜ(𝑎 + jb) = 𝑎, and ℑ is the imaginary part, so ℑ(𝑎 + jb) = b. The abscissa of convergence for these trigonometric functions is zero. Note that tangent function does not have a Laplace transform because the corresponding integral \eqref{EqLaplace.1} diverges.

■

Finally, we present some examples of

matlab codes involving the Laplace transform.

Example 5:

We present some examples to show how matlab can be helpful in dealing with Laplace transformation and its applications. We start with t4sin(𝑎t):

\[

{\cal L} \left[ t^4 \sin (at) \right] = \frac{24 a \left( a^4 -10 a^2 \lambda^2 + 5\lambda^4 \right)}{\left( a^2 + \lambda^2 \right)^5} .

\]

syms t a lambda

l=(t^4)*sin(a*t);

laplace(l,t,lambda)

>> ans =

(24*a)/(a^2 + lambda^2)^3 - (288*a*lambda^2)/(a^2 + lambda^2)^4 + (384*a*lambda^4)/(a^2 + lambda^2)^5

syms t x s

syms a positive

x = laplace(diff(diff(t^(4) * sin(a*t),t,t)), t, s)

simplify(x)

>> ans =

(24*a*s^3*(a^4 - 10*a^2*s^2 + 5*s^4))/(a^2 + s^2)^5

matlab is able to find the Laplace transform of the derivative:

syms t a lambda

fd=diff(t^(50),2);

laplace(fd,t,lambda)

>> ans =

30414093201713378043612608166064768844377641568960512000000000000/lambda^49

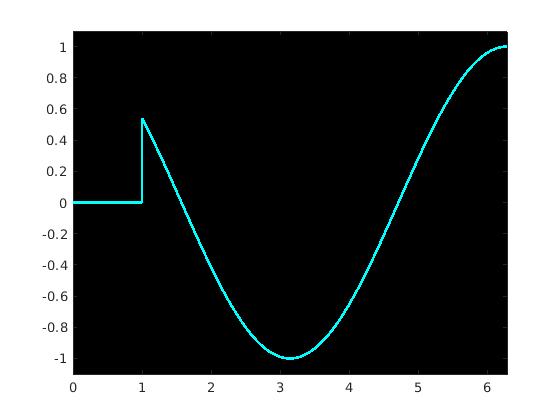

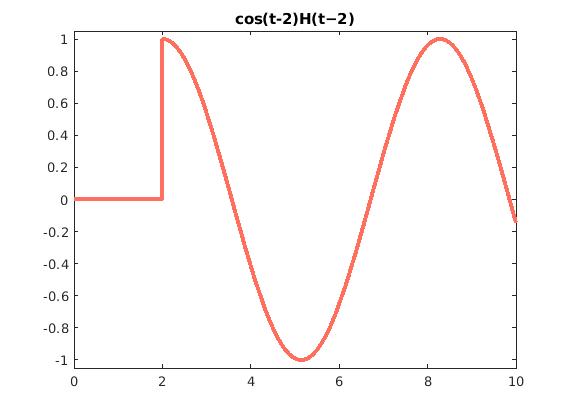

There are two kinds of delayed functions. Let us consider a familiar trigonometric function: cos(t). We construct from it two delayed functions: f(t) = cos(t)H(t−𝑎)

and g(t) = cos(t−𝑎)H(t−𝑎).

syms t

fplot(cos(t)*heaviside(t - 1), [0, 2*pi], 'c', 'Linewidth',2)

set(gca,'Color','k')

ylim([-1.1 1.1])

fplot(heaviside(t-2)*cos(t-2), 'color', '#FE6F5E', 'LineWidth', 3)

set(gcf,'color','[0.85 0.88 0.85]');

title('cos(t-2)H(t−2)')

xlim([0 10])

ylim([-1.05 1.05])

|

|

|

|

Graph of cos(t)H(t−𝑎)

|

|

Graph of cos(t−𝑎)H(t−𝑎).

|

Their Laplace transforms are different, as

matlab reports:

syms a s t

assume(a, 'positive')

laplace(heaviside(t-a)*cos(t), t, s)

>> ans =

-(exp(-a*s)*(sin(a) - s*cos(a)))/(s^2 + 1)

and

syms a t s

assume(a, 'positive')

laplace(heaviside(t-a)*cos(t-a), t, s)

>> ans =

(exp(-a*s)*sin(a)*(cos(a) + s*sin(a)))/(s^2 + 1) - (exp(-a*s)*cos(a)*(sin(a) - s*cos(a)))/(s^2 + 1)

\[

{\cal L} \left[ f(t) \right] = {\cal L} \left[ \cos (t)\, H(t-a) \right] = \frac{\lambda\,\cos a - \sin a}{1 + \lambda^2}\, e^{-a\lambda} .

\]

and

\[

{\cal L} \left[ g(t) \right] = {\cal L} \left[ \cos (t-a)\,H(t-a) \right] =

\frac{\lambda}{1 + \lambda^2}\, e^{-a\lambda} .

\]

Our next example is a periodic function

\[

f(t) = H\left( 2\,\sin t \right) .

\]

You will learn in section iv how to handle this case; however, we want to demonstrate the power of Mathematica in determination of the Laplace transform for complicated functions.

|

|

|

We plot the periodic step function,

syms t

plot(heaviside(2*sin(t)), [0, 10*pi], 'r', 'Linewidth',2)

ylim([-0.05 1.05])

for which we find its Laplace transform:

|

\[

{\cal L} \left[ H\left( 2\,\sin t \right) \right] = \frac{\lambda}{1 + e^{\pi\lambda}}\, e^{\pi\lambda} .

\]

The Laplace transform of the arctangent function is expressed through two special functions, called sine integral, Si(x), and

\[

\mbox{Si}(x) = \int_0^x \frac{\sin t}{t}\,{\text d}t \qquad \mbox{and} \qquad \mbox{Ci}(x) = \int_x^{\infty} \frac{\cos t -1}{t} \,{\text d}t

\]

called called

cosine integral.

syms a t s

assume(a, 'positive')

laplace(atan(t/a), t, s)

>> ans =

laplace(atan(t/a), t, s)

So we see that

matlab cannot handle this case---you need to find other resourses.

\[

{\cal L} \left[ \arctan \left( \frac{t}{a} \right) \right] = \frac{\sin (a\lambda )}{\lambda}\,\mbox{Ci}(a\lambda ) + \frac{\cos (a\lambda )}{\lambda} \left[ \frac{\pi}{2} - \mbox{Si}(a\lambda ) \right] .

\]

Now we give an example of application of the inverse Laplace transform.

syms t s

ilaplace(4/s/(4 + s^2), s, t)

>> ans =

1 - cos(2*t)

Another way to find the inverse Laplace transform is to break the function into a sum of simple terms:

syms s

partfrac(4/s/(4 + s^2), s)

% checking:

laplace(2*sin(t)^2, t, s)

>> ans =

1/s - s/(s^2 + 4)

syms t a lambda

f=2*(sin(a*t))^2;

laplace(f,t,lambda)

>> ans =

(4*a^2)/(lambda*(4*a^2 + lambda^2))

■