Preface

When an initial value problem has a solution that cannot be obtained from the general solution by choosing an appropriate value of an arbitrary constant, then such solution is called the singular solution. In this case the initial value problem has multiple solutions and uniqueness fails.

Return to computing page for the second course APMA0340

Return to Mathematica tutorial for the first course APMA0330

Return to Mathematica tutorial for the second course APMA0340

Return to Mathematica tutorial for the third course APMA0360

Return to the main page for the course APMA0330

Return to the main page for the course APMA0340

Return to the main page for the course APMA0360

Return to Part II of the course APMA0330

Glossary

Singular Solutions

Consider a first order differential equation

Obviously, an initial value problem with multiple solutions may be not suitable for modeling because it confuses a software in use. In applications, when uniqueness of solutions is required, singular solutions must be eliminated.

One of the common ways to determine existence of a singular solution is to eliminate c from the system of equations:

Constant functions are usually not solutions of the differential equations unless they annihilate the slope function. In this case, we call them critical points or equilibrium/stationary solutions. Therefore, if y = y* vanishes the slope function, \( f(x, y^{\ast} ) \equiv 0 , \) then y = y* is the equilibrium solution of the differential equation \( y' = f(x, y ) . \) A stationary solution may be singular or not, which we will show in the following examples.

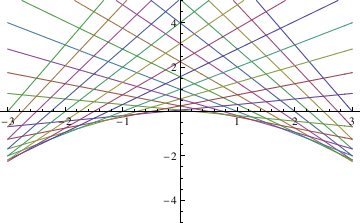

y=xy' + (y')^2

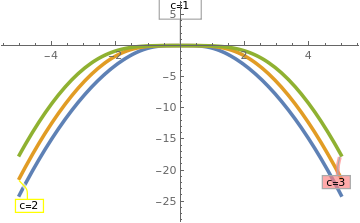

y[x_] = x c + c^2

samples =Table[y[x],{c,-3,3,1/4}]

Plot[Evaluate[samples],{x,-3,3},PlotRange->{-5,5}]

Out[19]= {9 - 3 x, 121/16 - (11 x)/4, 25/4 - (5 x)/2, 81/16 - (9 x)/4, 4 - 2 x,

49/16 - (7 x)/4, 9/4 - (3 x)/2, 25/16 - (5 x)/4, 1 - x,

9/16 - (3 x)/4, 1/4 - x/2, 1/16 - x/4, 0, 1/16 + x/4, 1/4 + x/2,

9/16 + (3 x)/4, 1 + x, 25/16 + (5 x)/4, 9/4 + (3 x)/2,

49/16 + (7 x)/4, 4 + 2 x, 81/16 + (9 x)/4, 25/4 + (5 x)/2, 121/16 + (11 x)/4, 9 + 3 x}

Out[20]=

To find the singular solution (envelope), we type:

Eliminate[{x==-f'[t],y==f[t]-t*f'[t]},t]

|

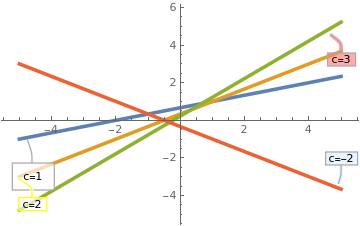

Now we plot some representatives from the general solution.

Plot[{Callout[(x + 2)/3, "c=1", Above, Frame -> True,

FrameMargins -> 10],

Callout[(4*x + 2)/6, "c=2", Below, Frame -> True,

CalloutStyle -> Yellow],

Callout[(9*x + 2)/9, "c=3", Right, Frame -> True,

Background -> Pink],

Callout[(4*x + 2)/(-6), "c=-2", Right, Frame -> True,

Background -> LightBlue]}, {x, -5, 5},

PlotStyle -> Thickness[0.01]]

|

|

| The family of solutions. | Mathematica code |

■

|

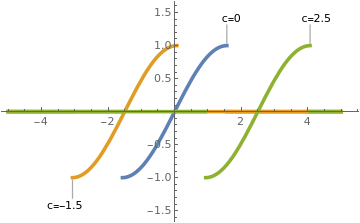

y1[x_] = Piecewise[{{0, x < -Pi/2}, {Sin[x], -Pi/2 <= x <= Pi/2}, {0,

x > Pi/2}}];

y2[x_] = Piecewise[{{0, x < -Pi/2 - 1.5}, {Sin[x + 1.5], -Pi - 1.5/2 <= x <= Pi/2 - 1.5}, {0, x > Pi/2 - 1.5}}]; y3[x_] = Piecewise[{{0, x < -Pi/2 + 2.5}, {Sin[x - 2.5], -Pi + 2.5/2 <= x <= Pi/2 + 2.5}, {0, x > Pi/2 + 2.5}}]; Plot[{Callout[y1[x], "c=0", Above], Callout[y2[x], "c=-1.5", Below], Callout[y3[x], "c=2.5", Above]}, {x, -5, 5}, PlotStyle -> Thickness[0.01]] |

|

| Three members of the general solution. | Mathematica code |

One of these curves from the primitive F(x, y, y') = 0 can be chosen to satisfy the initial condition y(x0) = y0:

|

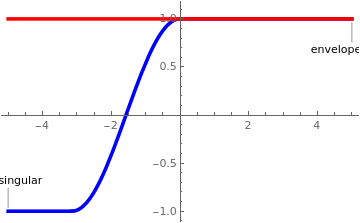

Now we plot the singular solution (in blue) along with the singular envelope (in red).

s[x_] = Piecewise[{{1, x > 0}, {Cos[x], -Pi <= x <= 0}, {-1,

x < -Pi}}];

env[x_] = 1; Plot[{Callout[s[x], "singular", Left], Callout[env[x], "envelope", Right]}, {x, -5, 5}, PlotStyle -> {{Blue, Thickness[0.01]}, {Red, Thickness[0.01]}}] |

|

| Singular solution and the envelope. | Mathematica code |

The equilibrium solution y = 1 is a singular envelope for the family of general solutions. ■

The given equation admits the explicit solution

|

Now we plot several singular solutions.

Plot[{Callout[(x + 2)/3, "c=1", Left, Frame -> True,

FrameMargins -> 10],

Callout[(4*x + 2)/6, "c=2", Below, Frame -> True,

CalloutStyle -> Yellow],

Callout[(9*x + 2)/9, "c=3", Right, Frame -> True,

Background -> Pink],

Callout[(4*x + 2)/(-6), "c=-2", Right, Frame -> True,

Background -> LightBlue]}, {x, -5, 5},

PlotStyle -> Thickness[0.01]]

|

|

| Three singular solutions. | Mathematica code |

■

- Show that y′ = yp, where p is a constant such that 0 < p < 1 has the trivial solution y = 0 and \( \displaystyle \quad y = \left[ \left( 1-p \right) \left( x+c \right) \right]^{1/(1-p)} . \)

- Find the general solution of dy/dx = y³. Is y = 0 a singular solution?

- Coddington, E.A. and Levinson, N., Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations, McGraw-Hill; 1st edition, 1984.

- Dobrushkin, V.A., Applied Differential Equations: The Primary Course, Second edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2021.

- Hale, J.K., Ordinary Differential Equations (Dover Books on Mathematics), Illustrated Edition, 2009.

- Ince, E.L., Ordinary Differential Equations (Dover Books on Mathematics) Illustrated Edition, 1956.

Return to Mathematica page

Return to the main page (APMA0330)

Return to the Part 1 (Plotting)

Return to the Part 2 (First Order ODEs)

Return to the Part 3 (Numerical Methods)

Return to the Part 4 (Second and Higher Order ODEs)

Return to the Part 5 (Series and Recurrences)

Return to the Part 6 (Laplace Transform)

Return to the Part 7 (Boundary Value Problems)